Schwarzman Scholars worked together to create an academic journal, reflecting their ability to think critically about the Middle Kingdom and the implications of its rise. These collections of thoughts come together to form “Xinmin Pinglun,” our Journal dedicated to the publication of the informative and analytical essays of our scholars. As the application deadline for the class of 2019 is approaching and the arrival of the incoming class is on its way, we are sharing pieces from Ximin Pinglun to give insight into the critical thinking and scholarship taking place at Schwarzman College. Here, Cameron Hickert, (Class of 2017) discusses the ongoing space race between China and India.

The Cold War-era space race represented the epitome of competition in a bipolar world: two major powers each flexing their military might, technological savvy, and cultural capital in an effort to secure space superiority over the opposition. Yet this race ended with the fall of the Soviet Union, and it appeared the global space order had shifted.

Now, with China’s resurgence on the world stage, space policy thinkers have raised the specter of a new space race, this time between the U.S. and China. But political leaders and experts on both sides of the Pacific Ocean in the past decade have increasingly dismissed that idea as a fanciful one; such a zero-sum model seems incompatible with China’s focus on developing a New Type of Great Power Relations (xinxing daguo guanxi, 新型大国关系) with the United States, and is equally at odds with the U.S. policy line of embracing China’s peaceful rise.

The more interesting competition for space superiority now lies on the level of regional order, as China and India develop growing capabilities in this sector, and place greater emphasis on space related achievements. As rapidly developing nations with a knack for quick-paced technological progress, both China and India are putting their scientific know-how to use in space as a means of increasing regional prestige and bolstering national capabilities.

In the border-less outer space environment, the U.S.’s status quo role as the global space superpower necessitates it making strategic decisions about its involvement (or lack thereof ) in the Chinese and Indian space programs. Indeed, as the space industries in these two Asian nations have matured, this has already been the case, with varying levels of success for all parties involved. The U.S. has a limited range of mechanisms by which to interact with the Chinese and Indian space programs; the more plausible pathway to engage with China is via political and people-to-people partnerships, while technological assistance is the more feasible scenario for involvement in the Indian case. But while both of these pathways are available, the U.S. would fare better if it indeed participated in increased people-to-people and political partnerships with Chinese counterparts, while avoiding sharing technology with the Indian space effort.

The U.S. has stood as the dominant space power for decades now, overseeing a time of rapid technological advancements and increased reliance on space for military, economic, scientific, and social uses. Based on spending levels, this appears unlikely to change for at least the next several years. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in the United States had a budget of over $18 billion in 2016, and that does not include U.S. expenditures on space efforts via other means such as military or intelligence funding channels. This amount is estimated to be greater than the space-related expenditures of the next five nations combined. China, meanwhile, is expected to spend around $6.1 billion annually on space efforts, and India lags further behind, allocating only $1.2 billion to the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) in the 2015-2016 fiscal year. But this is not to say that the U.S. has control over international space developments. China’s 2007 anti-satellite missile test, which greatly frustrated U.S. officials, is just one example of how U.S. capabilities by no means grant it unchallenged control in the space sector. Rather, the superiority of U.S. space abilities provides a greater incentive for nations seeking to grow their own programs.

The new space race

The regional rivalry between India and China has long simmered, and the next frontier increasingly appears to be space. Although officials on both sides of the border have denied the existence of a space race between the two nations, this claim is increasingly dubious. Recent events present the first counter: in response to China’s 2007 anti-satellite test, the ISRO formed the Integrated Space Cell to manage its future military space assets, and pledged to develop ground-based anti-satellite weapons. Days after China announced it would send a human into orbit in 2003, then- Prime Minister of India Atal Vajpayee publicly urged his nation’s scientists to land a man on the moon. It is also in this intensified climate that India’s space budget has increased by double-digit percentages. Economic rationale provides another reason to believe a competition is afoot. China has offered its global satellite-navigation services to countries participating in its One Belt, One Road (OBOR) infrastructure plan; India, which has been skeptical about OBOR, is developing a satellite system which could compete with the Chinese offerings. And as a greater number of private companies seek entry into space-related operations, the two nations will be vying against each other to attract the same paying customers.

Both sides increasingly are adopting rhetoric tied to a space race. Wu Yanhua, vice administrator of the China National Space Administration (CNSA), in the first half of 2016 stated his organization aimed “to rank among the world’s top three (alongside the U.S. and Russia) by around 2030”. Evident within this statement is a competition in which India falls short of China’s achievements. More explicitly, the Global Times – a nationalist and populist outlet for the Communist Party of China (CCP) – in February described a successful Indian satellite launch with the title, “India’s satellite launch ramps up space race.” The article then describes Sino-Indian competition in both military and commercial spheres.

India, meanwhile, has been heralding space achievements in such a manner that the subcontinent’s press, believing the Indian mission to Mars was meant to show China it was a worthy rival, reacted with forthright nationalism in the event’s wake. The government’s decision to use the Mars orbiter as the new design for the 2,000 rupee note lends further support to patriotic conceptions of a space competition between the Asian neighbors. Whether or not either nation’s top leadership declares a space race, the tit-for-tat timing of space-related developments, economic competition, and the rhetoric present at other levels of government and society indicate a race is indeed occurring.

From a fundamental ‘hard power’ perspective, the appeal of outer space is clear. Satellites are crucial to modern day capabilities in the realm referred to as ‘C4ISR’ – command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance. And while there are currently international prohibitions on the deployment of nuclear weapons, conventional weapons do not yet have these limits, although there is a precedent against deploying them to space. Indeed, the theories of deterrence that have long applied to terrestrial combat are now inextricably linked in a complex web with space, nuclear weapons, and conventional weapons. The value of crossover technologies is another important reality for China and India. Experts estimate that upwards of 90% of technologies developed during a space program have applications elsewhere. These cross-applications of the research and development fueling the space race is a means by which nations can improve domestic quality of life, produce technologies more suited to compete in a global environment, sharpen military capabilities, and improve domestic innovation.

“The regional rivalry between India and China has long simmered, and the next frontier increasingly appears to be space.”

Beyond the hard power dimension, this regional space race has taken on many of the soft power characteristics of the competition between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. during the Cold War. It should not be forgotten, “a major factor in the Asian space race is prestige, as rapidly developing countries there use technology to jockey for status. Space technology in particular, being flashy and complex, often captures the most cache.” Because soft power is about perception and attraction, demonstrating prowess in space capabilities is a crucial step in building this power regionally. Many of the feats that China and India are pursuing have already been achieved by the U.S., so mistakes are costlier in terms of international credibility – failures are perceived as worse when another nation has already been successful. Yet the attraction power of spaceflight achievements is more lucrative than in the past, as private entities around the world face tighter competition and shorter timelines in launching satellites, and are therefore willing to bring their business to any nation that can demonstrate the ability to launch cargo safely and cheaply. A prime example is India’s recent launch of 20 satellites on a single rocket; this mission included satellites from around the world, including the United States. The increased soft power borne out of a successful space program therefore is not only useful in the struggle for regional prestige, but also paves the way for increased economic success in a fast-growing industry.

China

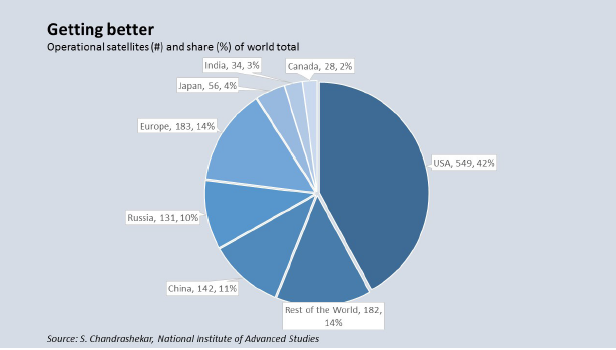

Chinese space policy recognizes the benefits to hard and soft power from pursuing a space program, and is making strides in space capabilities accordingly. China has now overtaken Russia as the second most important player in space – although Europe’s programs collectively have launched more satellites than China’s, they face difficulties in internal cohesion that present challenges in dealing with the rapidly-evolving global space order. In terms of pure capabilities, the CNSA and military maintain superiority over their Indian counterparts, although India is making significant strides in a lower-cost space strategy that this paper will analyze in later paragraphs. The diagram on the next page makes clear the strength of the Chinese space program, as measured by operational satellites. Certainly there are innumerable other metrics by which to calculate space capabilities, and many aspects of a space program evade quantification altogether. The multipurpose functions of satellites, however, allow them to operate in some ways as a sort of ‘currency’ by which to measure and compare space development across national boundaries.

China’s stated strategy for pursuing space development – as well as analysis from experts studying the nation’s behavior and progress in the sector – indicates the CCP is pursuing the hard power and soft power benefits associated with space programs, which lends further credence to the theoretical analysis underlying this paper. In 2007, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao summed up the CCP’s strategy rather succinctly following the success of China’s Chang’e 1 orbiter, stating that the mission “demonstrates that our comprehensive national strength, our creative capabilities and the level of our science and technology continues to increase, with extremely important practical implications… for strengthening the force of our ethnic solidarity.”

China’s regional interests guide some more specific development aspects of the NSA’s work. The overall framework for this is cast in the light of shifting Chinese military forces towards fighting ‘informationized’ wars. The PLA has maintained this doctrine since 1993, when strategists observed the U.S. successes in the 1991 Gulf War, and coined the ‘informatization’ paradigm to shape Chinese military modernization in line with hybrid warfare capabilities. C4ISR, long-range precision missile strikes, and joint force integration are “impossible without substantial and varied space capabilities. As China continues to develop and play a larger role in regional and international spheres, it is unlikely to slow down or change this space development strategy significantly. With specific importance to regional politics, Beijing has greatly increased its satellite involvement in the contested areas of the South China Sea, as well as in the East China Sea. This suggests the national government is prepared to engage in long-term operations in both these regions, and seeks to closely monitor the developments there. Finally, the anti-access and area denial (A2/AD) tactics that China is increasingly using in offshore waters – particularly in the East China Sea – require advanced infrastructure across space, land, and sea, combined with significant large-scale exercises. Each of these increased capabilities demonstrates a clear pathway by which the Chinese space program opens the door for

increased force projection in the region, in alignment with national goals.

More than in the Indian case, the CCP’s soft power space strategy is directed not only towards the international community, but also towards the domestic audience. In terms of foreign signaling, the official rhetoric is one supporting scientific exploration and research “to benefit the whole of mankind” and “to enhance understanding of the Earth and the cosmos”. Yet contributing novel research or reaching milestones before Asian neighbors do also serves the purpose of reinforcing claims to regional dominance and preeminence among the regional power order, because it signals that China has technology, capabilities, and resources beyond other nations’ reach.

“Demonstrating prowess in space capabilities is a crucial step in building this power regionally.”

The internal messaging attributes of China’s space program are aimed at bolstering CCP legitimacy. Absent from internal and external analyses of India’s space program is evidence supporting a similar domestic function of the space agency. Of course, perceptions of government progress in the space race may contribute to more positive perceptions of the ruling party, which can have benefits during national elections, but the Indian government’s rhetoric is less focused on this component, and thus the relationship between this sort of internal soft power and government legitimacy is less tight than in the Chinese case. A very clear illustration of the government’s use of the space program as a soft power tool in China was the manned space capsule Shenzhou 6, which carried seeds from Taiwan as an assertion of China’s sovereignty. While Taiwanese seeds are most certainly not a military or economic tool, their political statement is quite clear.

Given this context, what might be a reasonable potential pathway for increasing U.S. cooperation with the Chinese space program? The current climate is quite frosty, so there simultaneously exists many possibilities, as well as many constraints. Due to concerns with security and technology- sharing, all NASA researchers are currently prohibited from working with Chinese citizens affiliated with a Chinese state enterprise or entity.

This includes using funds to host Chinese visitors at NASA facilities, which has become a particularly contentious issue regarding academic conferences the organization hosts annually. This is illustrative of the general U.S. concern about sharing technology, which is based on worries regarding intellectual property, economic advantages, and space-based capability superiority. It is this concern that has even pushed U.S. legislators to block China from joining the International Space Station (ISS), despite Chinese desires to do so. This reality, taken with the heavy Chinese strategic emphasis on boosting technological capabilities, means that the U.S. and China are unlikely to cooperate on the core of Chinese space development for the foreseeable future.

But this does not mean all opportunity for cooperation is lost. In fact, in light of greater tensions in other parts of the U.S.-China relationship, the boon of space cooperation might increasingly be of value to leaders of the two powers. The U.S.-Russian space cooperation provides an important precedent, in which the ISS serves as a major diplomatic link. As China presses forward with Project 921, which aims to create an international space station of China’s own in its final stage, there will be more opportunities for people-to-people cooperation that involve manning and managing space station programs. By cooperating on these issues, the U.S. and China could cultivate better diplomatic relations, while minimizing technological sharing risks that would dissuade the American side from getting involved. Furthermore, there exists a current pathway by which this cooperation can grow European and Russian space agencies.

The presence of the European and Russian space agencies as potential intermediaries furthers the possibility that such a collaboration could occur, and also decreases the risks the U.S. would add by joining in on such cooperation. If the ISS is already accessible to the Chinese, then the concerns of technological ‘leaking’ would not be significantly greater were the U.S. to get involved than in the alternate case. The technology Americans use aboard the ISS is unlikely to be very different from that of other ISS member nations, especially because technology aboard the space station must be compatible with the ISS itself.

An environment in which U.S. legislators perceive the space programs of other nations to be cooperating more greatly with Chinese collaborators boosts the odds of creating the political capital necessary to lower anti-China restrictions on space-related programming. Already China has been aligning more with U.S. interests in UN committees developing best practices for outer space, which is a significant shift that leaves Russia to play a more anti-American obstructionist role on its own. For example, last summer Beijing signed two agreements with the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs to help finance non-Chinese payloads and experiments on its future space station. Pushing this trend further could simultaneously allow the U.S. to achieve its strategic goals of maintaining the title of space superpower (China’s improved space capabilities would likely be perceived as supporting the U.S. order, rather than rising in rivalry to it), while China would be able to boost its own soft power via increased prestige and escalate its hard power via increased space expertise.

India

India’s space capability situation is quite different from China’s, but its assets are not insignificant. It boasts over 34 satellites in orbit and has successfully completed the least expensive inter planetary mission ever, by sending an orbiting craft to Mars for $73 million. However, from a capability perspective, India’s greatest shortfall is its lack of long range radars and laser ranging systems that can track space objects – this infrastructure is “extremely limited if not non-existent.” These systems are crucial to protecting space-based assets, as they allow space agencies to detect inactive satellites and space debris which might collide with sophisticated and costly equipment in orbit. These systems are also the basis upon which a nation can track anti-satellite weapons, and are thus crucial to defense capabilities and monitoring of other space powers.

Strategically, India’s approach appears to be noticeably different from China’s. Except for the new 2,000 rupee note and a laissez-faire approach to reigning in nationalist rhetoric in the press, absent are broad proclamations about the importance of space capabilities for national defense, human achievement, scientific prowess, economic power, and global prestige. Rather, the Indian government’s published materials regarding its space program’s vision, mission, objectives, and functions are quite sparse and utilize a technical vernacular rather than one dressed in trimmings of power proclamations. For example, the first point under the ISRO’s mission statement is to “design and development of launch vehicles and related technologies for providing access to space.” It is within the scope of a regional rivalry perspective that this makes sense; because India’s capabilities are not at the level of China’s, it would be unwise from a posturing position to emphasize the importance of those capabilities for national defense or regional stature. If India can continue to develop technological abilities that put them more on par with Chinese assets, it is likely to

grow increasingly public about the power implications for space technology.

One interesting strategic approach which seems to distinguish the ISRO is its emphasis on budget-friendly approaches to space. The unmanned rocket it sent to Mars for $73 million looks even more impressive in light of NASA’s Maven Mars mission, which cost $671 million. Furthermore, the success of this launch on relatively short timescales surprised Chinese space authorities, and thus garnered India more positive press and raised more eyebrows than would have been the case under a more traditional mission scheme. In fact, the ISRO often spends significantly less money than the government allocates to it annually; in the 2014-15 fiscal year it spent only $869 million when it was allocated $1.08 billion.

“The internal messaging attributes of China’s space program are aimed at bolstering CCP legitimacy in the nation.”

Aiding the Indian economic emphasis in its space program is Pakistan’s relative weakness in the arena. Many facets of these nations’ military endeavors – for example, their nuclear programs – are best understood in relation to the other, yet Pakistan’s Space and Upper Atmosphere Research Commission (SUPARCO – the nation’s space agency) has fallen far behind ISRO’s accomplishments and ambitions. In contrast to India’s record of launching 104 satellites in a single mission, SUPARCO is not expected to have the capabilities to indigenously produce or launch its own satellite for two decades – the target is currently set at 2040. These factors have enabled a relatively frugal Indian approach that is unique among major space powers today, and represents a noticeable shift from the paradigm set under the Chinese and U.S. approaches.

As the regional space race moves into the future, it is plausible that the U.S. involvement in India’s program takes the shape of technology sharing. India could certainly benefit from more rapid development of its tracking technologies, and the U.S. is increasingly seeking to cut costs from NASA in development of a leaner space program. Taken in a vacuum, collaboration between the two on technological ends would thus seem quite positive, and even natural. Already both nations are active in bilateral space cooperation, so further integration is not impossible.

Yet in light of regional power politics, deep technological cooperation – particularly regarding space tracking capabilities – would be imprudent for the United States. Due to the current political climate between the U.S. and China in regards to space cooperation, the partnership with India would appear negatively. This is also true against the backdrop of South China Sea involvement in which the U.S. is currently a factor, as well as ongoing border disputes between China and India. Because China sets such a strong emphasis on the power implications of the regional space order, as well as the reality of the military-civilian dual uses of space technology, stronger U.S.-India cooperation on this front would almost surely antagonize Beijing. This is in contrast to India’s approach, which finds a more solid grounding in the economic aspects of the regional space race.

The implications of U.S.-India technological cooperation would be a heightened risk environment in the region, and potentially a more belligerent China on security issues; both of these would be negative outcomes for the U.S., and would cause India more risk. It would also escalate the security and military aspects of the regional space race to a new level, stirring tensions and undermining the possibility of enhanced regional cooperation in the near future. Political ramifications outside the region are also possible, as China might seek to block India from the sort of partnerships it has been developing with Europe and Russia.

Although this would not be a problem as of now – India does not seem intensely focused on space station access or capabilities – it would crystallize an environment unfriendly to burgeoning Indian capabilities in the coming decades. Avoiding technological transfer to both China and India would also enable the U.S. to avoid growing any perceived role in the India-Pakistan relationship, in which both nations would resent any technological support provided to the other. U.S. technological assistance to India would irk Pakistan, and the China-Pakistan relationship could produce anti-American sentiment in India if U.S. technological assistance to China were to seep into SUPARCO’s hands. Finally, because the space industry in India is still in its early stages and is tightly interwoven with commercial interests, the risks that U.S. technology shared in partnership with India then disseminate to actors and areas unfavorable to the United States is a stark possibility.

Favoring people-to-people and political partnerships with China above technological cooperation with India may appear to undercut positive momentum built under the U.S.-India Civil Nuclear Agreement, but that is not the case. Similar to its economy- focused approach to space-related developments, India continues to uphold economic success as its core goal. This not only means the civil nuclear deal the U.S. Congress ratified in 2008 may not have earned the U.S. as much pull as some had expected, but also that India is unlikely to sabotage economic ties with China on behalf of U.S. interests. The year after the framework for the nuclear deal was announced, China and India declared China-India Friendship Year. Even after India participated in some military exercises in the South China Sea upon signing a joint communiqué with the U.S. stating “the importance of safeguarding maritime security and ensuring freedom of navigation and overflight throughout the region, especially in the South China Sea,” India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi made it extremely clear that his first, second, and third priorities were the advancement of India’s economy.

“The regional space race in Asia is alive and well.”

The regional space race in Asia is alive and well, with China and India developing an increasingly fast-paced rivalry. Within this context, there exists clear differences in approaches between the two nations: China is open in its power-based rationale (including both hard and soft power) for the space program, which is targeted at both domestic and foreign audiences, while India is much more circumspect and technical in its official rhetoric and strategy. These dissimilarities make sense within the frameworks of the existing strengths and shortfalls of each nation’s space program, and also drive the future aims of both nations as they continue to develop a space program encompassing military, economic, and scientific characteristics. The U.S., as the global space superpower, is always a factor in this competitive dynamic, and as such must be deliberate in its approach.

The most plausible possibilities for engagement with the two nations are quite different, with U.S.-China cooperation taking a more human and political line, while U.S.-India cooperation might be more likely to be technological in nature. However, only one of these two paths forward would be advisable. This sort of cooperation with India would have negative implications in light of the regional power struggle between the two Asian neighbors, and the signaling of that collaboration would be even more antagonistic in light of the current prohibitions limiting U.S.-China partnerships. However, by approaching China through more limited human and political channels – some of which might be widened through European or Russian intervention – the U.S. and China can build collaborative pathways in each nation’s interests, as well as in the interests of the broader space-faring community.

Cameron Hickert (Class of 2017) is from the United States of America, and graduated from the University of Denver.